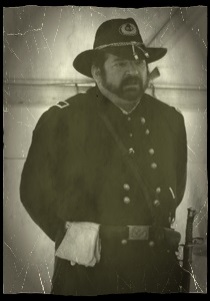

April 20, 2013 marks the 186th birthday of John Gibbon, career military man, and one of the most successful commanders of the Federal army, during the Civil War.

Born in Holmesburg, Pennsylvania, (now part of present day Philadelphia) on April 20, 1827, to Dr. John H. Gibbons and Catharine Lardner, he spent his early years in the Philadelphia area. When Gibbon was about seven years old, his family relocated to the Charlotte, North Carolina area, where his father became chief assayer of the U.S. Mint.

After his early education, Gibbon would be appointed to the Military Academy at West Point, in 1843. Graduating in 1847, he would be commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery. Gibbon would be in Mexico for the Mexican War, but would see no significant action. Later, he would be in Florida during the Seminole War. As an artillery instructor, as West Point, Gibbon would write, “The Artillerists Manual,” in 1859. He would next be sent west, to Utah, after the ‘Utah War’ with the Mormons. There he would be a captain in the 4th U.S. Artillery, stationed at Camp Floyd.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Gibbon would still be stationed in Utah. Although his father was a slave holder, Gibbon’s loyalty to the United States never wavered. Three of his brothers, two brothers-in-law and a first cousin, J. Johnston Pettigrew (who would be a Confederate Brigadier General) would all fight for the Confederacy. Gibbon would later face his cousin Pettigrew in battle on the third day at Gettysburg when Pettigrew’s brigade was part of ‘Pickets’ Charge. Brought quickly to the eastern theater, Gibbon would become chief of artillery for US Brigadier General Irvin McDowell’s division. He would be promoted brigadier general of volunteers on May 2, 1862. Taking command of an all Western brigade, with regiments from Wisconsin, and Indiana, Gibbon would mould them into a fighting machine. Often considered a strict disciplinarian, he would take good care of his troops, making sure they received adequate rations and equipment – for this, he was well respected by his men.

With the brigade’s new uniforms, sporting pre-war black U.S. Army Hardee Hats, that Gibbon officially requisitioned, the brigade would be called the “Black Hat Brigade.” With the formation of US Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia, Gibbon’s Fourth Brigade would be assigned to US Brigadier General Rufus King’s First Division of McDowell’s III Corps. In late August 1862, Pope’s Army of the Virginia was searching for CS Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s 2nd Corps, which had been detached from CS General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, to prevent Pope from combining forces with US Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. At the Battle of Cedar Mountain, on August 9, Jackson’s forces would defeat a detachment of Pope’s forces, commanded by US Major General Nathanial Banks.

After the battle, Pope believing that Jackson had moved to Centreville pushed his two corps northeast to battle them, before the rest of Lee’s army could arrive. With McDowell’s III Corps pushing east on the Warrenton Turnpike, towards Centreville, on August 28, they would be surprised by a flank attack near the First Bull Run battlefield. Gibbon’s brigade would be right at the center of what would be called the battle of Brawner’s Farm. With support from US Brigadier General Abner Doubleday’s Second Brigade, Gibbon’s western men would hold the majority of one of Jackson’s divisions, at bay, for over two hours. The battle at Brawner’s Farm would be the start of the second battle of Bull Run. Gibbon’s “Black Hat” brigade performed extremely well, but was badly mauled. They would see little additional action, during Second Bull Run, being held in a reserve capacity. Unfortunately, for the Federal army, Lee was able to reunite his entire Army of Northern Virginia, crushing Pope’s Army of Virginia, on the fields of Bull Run. Like the aftermath of First Bull Run, Second Bull Run was a complete rout, with the Federal armies streaming back to Washington City, and Alexandria, Virginia. Lee however, turned north, determined to invade Northern soil, and recruit new soldiers in Maryland.

In Washington, Abraham Lincoln, much to the consternation of his Cabinet (the Cabinet believed that McClellan withheld reinforcements from Pope causing the defeat at Second Bull Run), would place McClellan in charge of the now combined Army of the Potomac, that included the remainder of Pope’s army. Pope would be shuttled off to a rural command, in Minnesota. McClellan’s reconstituted army quickly pursued Lee, on a parallel path, into Maryland. Lee, being west of South Mountain, near Frederick, had the mountain passes, from the east, well protected. On September 14, at what would be known as the battle of South Mountain, Gibbon’s brigade would earn a new moniker – “Iron Brigade” – for its offensive action at Turner’s Gap. Facing over 5,000 Confederate troops, commanded by CS Major General Daniel Harvey Hill, on the National Road, the Iron Brigade forced their way through the gap. They received valuable support from three divisions of US Major General Joe Hooker’s I Corps, positioned north of Turner’s Gap. Overnight, Lee would withdraw his troops, from the South Mountain Passes, after Crampton’s Gap was captured by the Federal army. Gibbon’s brigade, badly bruised, was able to push through Turner’s Gap, on September 15, pursuing the Army of Virginia towards Sharpsburg, Maryland.

On September 17, 1862, George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac attacked Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle would be named after a meandering stream, east of town – Antietam. The carnage of that day exceeded any other one day loss our country has ever suffered; including Normandy, the Battle of the Bulge and Okinawa. Before dawn, on what would be a warm fall day, Joe Hooker’s I Corps prepared to assault Lee’s left flank, resting not far from the Dunker Meeting House (church). Gibbon’s Iron Brigade would take an active role in attacking Jackson’s 2nd Corps on this day, approaching through a cornfield. Wave after wave of Federal soldiers would pass through the “corn field” and be pushed back by Lee’s rugged fighters. Before the battle in that sector was over, the Iron Brigade would suffer terrific casualties, with their blood christening the field, which from thence forward would be known as a proper noun: The Corn Field. The men of the west, led by John Gibbon, would once again show their élan, their fighting spirit, their strength under fire – validating their status as the Iron Brigade.

The battle of Antietam would be fought to a draw, both sides holding roughly the same position they held before the fight. On September 18, there would be a short truce for each side to recover their wounded – and bury their dead. On September 19, McClellan would find the Confederate army gone. Lee had escaped over the Potomac, into Northern Virginia. McClellan dubbed it a great victory. Lincoln, and the civil authorities, were disturbed that McClellan did not push his tough fought victory, trapping Lee against the Potomac and decimating the army. The “draw,” however, was good enough for Lincoln to issue his war-time measure, the “Emancipation Proclamation,” essentially freeing all slaves, in areas actively rebelling against the Federal government, on January 1, 1863. The objectives of the war had changed.

After the battle of Antietam, John Gibbon would move to division command, commanding the Second Division of US Major General John F. Reynolds’ I Corps. At Fredericksburg, Gibbon’s division would participate in the fighting with US Major General William Franklin’s Left Grand Division. They would attack a well fortified position, commanded by CS Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Like every other action, in the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Federal army would be repulsed – time, after time, after time. The battle was considered a debacle, with the army commander, US Major General Ambrose Burnside, being removed from command, shortly after the battle. Gibbon would be wounded leading his division, a minor wound that would take a significant time to heal.

Returning to his command, in the spring, Gibbon would find the Army of the Potomac had a new commander, US Major General “Fighting” Joe Hooker. Hooker had planned a flanking move, west of Fredericksburg, that would allow all his corps, less US Major General John Sedgwick’s VI Corps held in Fredericksburg as a diversion, to fall on Lee’s rear, destroying his army. Unfortunately, at the battle of Chancellorsville, Hooker’s plans fell apart and the Army of the Potomac would suffer another terrible defeat. Robert E. Lee was able to divide his army, and with Jackson’s 2nd Corps attack Hooker’s right flank, rolling it up. Gibbon’s division saw little action as they were held in reserve. As in September 1862, after his victory at Second Manassas, Lee determined to take his army north of the Mason-Dixon Line. With Hooker’s Army of the Potomac having retreated north, licking its wounds, Lee, hidden by the Shenandoah Mountains, pushed into Pennsylvania in late June.

Meanwhile, Hooker having difficulty determining a strategy for expelling Lee from the North, was removed from command. Taking over command, several days before the largest battle on American soil, US Major General George Gordon Meade would push his Army of the Potomac north, feeling for Lee. Unfortunately, Lee’s army would find the Federal cavalry, commanded by US Brigadier General John Buford, at Gettysburg on July 1. Having arrived there before the Federal infantry, Buford was able to hold an entire Confederate division, commanded by CS Major General Henry Heth, at bay, until reinforcements could arrive. The I Corps, commanded by US Major General John F. Reynolds arrived first, followed closely by US Major General Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps. Reynolds would be killed early in the action. Fortunately, the new II Corps’ commander, US Major General Winfield S. Hancock, arrived to take over the rapidly deteriorating position. He would pull the army back through Gettysburg, and fortify Culp’s Hill, south of Gettysburg, with his II Corps making up the left flank of the army, extending south along Cemetery Ridge. Commanding the Second Division of Hancock’s II Corps, Gibbon was very involved, at times commanding the entire corps, placing the troops of the II Corps. The placements were very good and would have a significant impact on the outcome of the Battle of Gettysburg, on July 3. After having been, if not repulsed, significantly held during actions on both Federal flanks, on July 2, Lee determined overnight that Meade had weakened his center during the fighting on July 2, so he would attack the center of Meade’s line on July 3. In what would become known as Pickett’s Charge, after CS Major General George E. Pickett, Lee sent close to two divisions across the open ground towards the center of Hancock’s II Corps, holding Cemetery Ridge.

Meade had predicted this, stating to Gibbon after a late night meeting, with his commanders, “If Lee attacks tomorrow; it will be on your front.” Meade’s warning to Gibbon was very prescient. His division would be at the epicenter of Pickett’s attack. Fortunately, both Hancock, and Gibbon, had prepared their defensive line well. The II Corps was able to turn Pickett’s Charge, inflicting terrible losses on the Confederates, with only a few soldiers breaking the Federal line. Of these was CS Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead, a close friend of Hancock’s, from before the war, who would be mortally wounded leading his troops toward a Federal cannon. Both Hancock, and Gibbon, would be wounded at Gettysburg. Hancock’s wound proved more serious and troubled him for the rest of his life. Gibbon was able to recover, and join his division, before the spring campaign season of 1864. While recovering he would command a draft department in Cleveland. In November, Gibbon would travel back to Gettysburg, and be at the dedication of the National Cemetery. He and friend, Frank Haskell, also witnessed Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

In May 1864, Gibbon now back in command of his II Corps’ Division, would participate in the bloody battles soon to take place in Virginia. With a new overall commander, US Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, the action was sure to be fast, and brutal. Grant had come from the west, after many successful battles, and the capture of two Confederate armies, to take over command of all Federal land forces. Instead of having his headquarters in Washington City, Grant chose to have a field office with the Army of the Potomac, nominally under the command of Meade. In the Overland Campaign, Gibbon’s division, and the rest of the II Corps, would participate in the bloodiest string of battles of the Civil War: The Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna and Cold Harbor. While accumulating huge losses, estimated at 60,000 of all types, Grant’s tactical plan was to continue to push past Lee’s right flank, eventually uncovering Richmond. If the opportunity to crush Lee’s army, outside field works, were given, he would take advantage of this.

Unfortunately, Lee was always slightly ahead of Grant, able to throw up impenetrable works, and abatis. After the slug fest at Cold Harbor, where Gibbon’s division would again suffer serious losses, Grant was able to make one of the most amazing change-of-fronts, which has ever occurred. With help from US Major General Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James, and US Major General Phil Sheridan’s cavalry corps, a major diversion was made, making Lee believe that Grant intended on fighting along the Cold Harbor line. In fact, Grant put his army on the move, crossing the Chickahominy River and the James River (a feat that required building a 2,100 foot pontoon bridge) and heading south towards Petersburg, Virginia. Gibbon would be promoted, major general volunteers, on June 7, for heroism leading his division, during the Overland Campaign.

With the Armies of the Potomac and James, now laying siege to Petersburg, and Richmond, Grant’s operational plan was to continue lengthening his lines south, and west, knowing that Lee was unable to cover his lines, with the forces he had available to him. Eventually a breakthrough point would be found and Grant would take advantage of it. No one would have thought that it would take ten months, and thousands of additional Federal casualties, for the breakthrough to take place. During this time, Winfield Scott’s II Corps would be sent on a mission, to destroy track of the Weldon Railroad, lengthening Lee’s supply lines. After pushing past Ream’s Station, on August 25, the II Corps would run into Confederate cavalry commanded by CS Major General Wade Hampton. Additionally, Hancock now faced the infantry of CS Lieutenant General A.P. Hill. Falling back to Ream’s Station, the II Corps fell behind crude fortifications, and would end up being badly beaten, in the battle called Second Ream’s Station. This would be the only battle that Hancock would lose, while in independent command. Gibbon was disheartened with his division’s performance, and would briefly command the XVIII Corps, of the Army of the James, before taking leave, due to sickness.

After rehabilitating, Gibbon would command the newly created XXIV Corps, assigned to the Army of the James. His corps would eventually help create the breakthrough that Grant had waited so long for, with the capture of Fort Gregg, on April 2, 1865. In combination with the recapture of Fort Stedman, and a Federal victory at Five Forks, on April 1, Lee would be forced to retreat, along the Appomattox River. During the final battle, at Appomattox Court House, Gibbon’s troops would block Lee’s only escape route, forcing his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant, on April 9, 1865. Gibbon would be one of three commissioners that would accept Lee’s formal surrender.

Gibbon would remain in the U.S. Army, after the Civil War. His rank would revert to Colonel in the regular army. Gibbon would command infantry, in Montana, and participate in the Indian Wars. In 1885 Gibbon would finally receive promotion to brigadier general regular army.

After returning east, Gibbon would become president of the Iron Brigade Association, and Commander in Chief of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. He would die in Baltimore, Maryland on February 6, 1896. He was 68. Gibbon is buried at Arlington Cemetery. His book, “Personal Recollections of the Civil War,” was published posthumously in 1928. Major General John Gibbon is a true American hero.

Robert E. Hanrahan, Jr.

Aside from being one the founding members of C.O.U.G. in 2002, Robert (Bob) E. Hanrahan, Jr. has a long history with Philadelphia civic and business communities.

He received his undergraduate degree in marketing from La Salle University (Class of 1975). Bob is currently a retired consultant in the information technology field. In 1997 Bob served as a consultant to AbiliTech, now known as InspiriTec, whose services provide assistance to the physically challenged.

In 1988, he pursued an opportunity with United Engineers and Constructors in Philadelphia, later known as Raytheon Engineers and Constructors. Bob worked on various projects at Raytheon, achieving the title of Information Systems Technical Specialist by 1993. In 1982, Bob joined LTI Consulting Company, which was soon acquired by General Electric. Bob continued with General Electric Consulting and earned the position of Senior Systems Analyst.

At an early age, Bob began working in the family’s construction related businesses, remaining active for several years after graduation. Upon receiving a programming certificate from Maxwell Institute in 1979, Bob joined the Pennwalt Corporation as a programmer, leading to a programmer/analyst position. While at Pennwalt, Bob became acquainted with a program to educate and offer job placement assistance to the physically challenged. This led him to pursue a consulting career he remains committed to with InspiriTec.

Bob’s late father (Robert E. Hanrahan Sr.) served in the U. S. Navy during World War II as a seaman 1st Class aboard the Battleship U.S.S New York, which engaged in numerous actions including the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Bob is also an active participant and member of the United States Naval Institute, including the Arleigh Burke Society and the Commodore’s Club. During the Civil War, Bob’s Great-Great Grandfather James Murphy, enlisted in the 20th P.V.I. for 90 days in April 1961, and then enlisted in the 6th U.S. Cavalry where he became a Sergeant in A Company and was honorably discharged in December 1862

Bob’s other present interests include his involvement with La Salle University as a member of the Presidents Council, Investments Committee Member of The William Penn Foundation; InspiriTec, Board Member; President of G.A.R. Sons of the Union Veterans Camp 299, The Heritage Foundation: Washington, D.C., Presidents Council Member; Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association, Board Member; Majority Inspector of Elections: Precinct 249, East Goshen Township, PA. The Longport Historical Society: Longport, NJ, Trustee, and Past President. The Civil War Preservation Trust, Friends of Historic Goshenville, Pennsylvania and National Republican Party.

Bob lives in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and has three children, Katherine born in 1985, John born in 1986 and Dorothy born in 1988.

Bob Hanrahan can be contacted at john.gibbon@uniongenerals.org.